I’m on a plane, tens of thousands of feet above the speeding ground of an indeterminate point in North America, headed for California to move forward with my writing, when it hits me: I spend a lot of time thinking about the past. A moment triggers a memory, and it pulls at me. I give in, let the memory play out in my head, try to look at it from a new angle. Whether it’s full of pain or joy, I experience it all over again, an echo of the original. But often with the power to steal me at length from the present and make people pause. Dana, did you hear what I just said? No—the answer is always no. I was somewhere else.

I’m on a plane, tens of thousands of feet above the speeding ground of an indeterminate point in North America, headed for California to move forward with my writing, when it hits me: I spend a lot of time thinking about the past. A moment triggers a memory, and it pulls at me. I give in, let the memory play out in my head, try to look at it from a new angle. Whether it’s full of pain or joy, I experience it all over again, an echo of the original. But often with the power to steal me at length from the present and make people pause. Dana, did you hear what I just said? No—the answer is always no. I was somewhere else.

At work lately, I’ve been immersed in articles on having a healthier and more mindful workplace environment, hearing experts talk about living more in the present. Focusing too much on the future brings anxiety; fixating on the past can lead to depression, they say. Being fully present in time produces the most happiness. I used to think this was because my brain sought closure. That once I figured out what I had missed the first, second, fiftieth time I processed the memory, the last puzzle piece would click in. I would be left with a full and complete understanding of what happened, what it meant or will mean for the future. And then I could focus more on what was in front of me. But maybe not.

“They” are the experts, so what do I know, right? But as I read an article quoting David Constantine, author of the short story that inspired the acclaimed movie 45 Years, something about that plane ride brought clarity that contradicts such a notion, at least in part. “If you survive long enough then the past is extraordinarily potent,” says Constantine. “I hate the idea of closure, I think it is a detestable idea. Things don’t get closed when you are dead. It’s not history that I write about, but a person’s life. And within that life nothing is ever dead and buried.”

His words connected with what’s been bubbling in me for some time: the past isn’t static—our memories don’t exist as some finite movie, moments of time captured and preserved, put in a jar for later viewing. The past is alive and breathing, evolving and changing as we do.

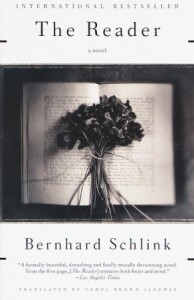

Bernhard Schlink talks about such living memories in his novel The Reader, about a man who tells the story of his adolescence, growing up in post-WWII Germany. In his youth, he has an affair with a much older woman. She vanishes from his life without notice, then reappears ten years later on the stand of a Nazi trial, accused of war crimes, as the now grown man is in law school and watches from the stands. He stares at her and experiences everything all over again, realizing the deep impact that relationship had, and continues to have, on his life. He cannot shake her presence, even with so much distance.

“The tectonic layers of our lives rest so tightly one on top of the other that we always come up against earlier events in later ones, not as matter that has been fully formed and pushed aside, but absolutely present and alive,” Schlink writes. “I understand this. Nonetheless, I sometimes find it hard to bear.”

There is truth there, I think, truth in declaring death to closure. And yet, as a culture, we crave it. We are obsessed with endings. How bad does a movie have to be before you will turn it off? You want to see how it ends, even if you don’t enjoy the story. You feel a pressing urge to witness the conclusion.

In books, films, television shows—I feel the same. I want to know how the writer imagined that last moment for the audience. However, when an ending is too neat, it ruffles me. I stop wondering about the characters, what happens to their lives once the cameras turn off. They become flat, two-dimensional, as opposed remaining alive off the page somewhere, which is what I want them to be.

The best endings, the (slightly) ambiguous ones, give the reader or viewer a jump-off point for the brain to colour in the possibilities. You are no longer experiencing those characters in real time, but they stay with you “absolutely present and alive.” With novels, these writers are creating outlines for us to bring the rest to life, full of our own perspective and history to tilt the story in our direction. To give it personal meaning and significance beyond the intended layers.

As a writer, I strive to understand how to map the ever-evolving movement of life’s layers, in order to create characters that are present and alive, with pasts that move and evolve as they do. As a human being, I must revisit my own past in order to understand the tectonic plates the present rests on. Otherwise, I’ll never see the earthquakes coming.