You’ve been gone a month. Everything I’ve been through in that time, I think, what would you do? How would you react? What decision would you make? The only answer that ever comes is that you wouldn’t hesitate. You would pick a path and follow through. Turn on your blinker, close your eyes and move the wheel. Never look back.

You’ve been gone a month. Everything I’ve been through in that time, I think, what would you do? How would you react? What decision would you make? The only answer that ever comes is that you wouldn’t hesitate. You would pick a path and follow through. Turn on your blinker, close your eyes and move the wheel. Never look back.

A bad way to drive but a good way to live.

I remember when they told me you had a bad heart. We were sitting in the hospital after they had drained your lungs of fluid the night before. I was wearing a blue silk blouse and brand new white jeans that I had spilled chocolate shavings on that morning from a protein bar. The stains are still there.

I almost laughed, because the statement was so ridiculous. You were all heart. You worried about the fact that I was missing work to be there with you. I held your hand and told you it didn’t matter. I could work from anywhere.

But I didn’t. I downloaded episodes of Golden Girls for you on my iPad and shared sections of The Globe and Mail and pretended not to notice when you fell asleep in front of both. I dealt every hand of 31 because you couldn’t remember how many cards we were supposed to have or what rules to follow. I had a boss who cared and colleagues who understood that I was exactly where I needed to be. There’s a lot to miss these days.

We waited for tests to tell us again what the doctors already knew. That valves were leaking and it was only going to get worse. I was already losing you.

You cried when I left most times. You didn’t understand what was happening and why you couldn’t just come with me. I felt like crying right along with you, because all I wanted to do was walk you out of there. But they told me I couldn’t. Not yet.

I couldn’t then and I couldn’t less than a year later, in a different hospital, in a different city, halfway across the country, when we thought the same thing was happening again. That it would be bad, but you would fight through it. This time I watched you struggle to breathe and see and take a sip of water. I held your hand and told you that you mattered. I told you that I loved you. I wondered if you knew I was saying goodbye. I tried to keep a smile on my face so you’d see only happy things whenever you would, could open your eyes. But I was falling apart every moment they closed because I was afraid of what I realized was coming next.

This isn’t what I want to write about. It’s not what I want to remember. Because the heart part is just bullshit. Because you were the best person who ever lived and loved and touched my life. Because I am better to have known you and worse to have lost you and I find myself somewhere in between, lost and wandering around. I can’t make a choice. I can’t close my eyes. I can’t turn the wheel.

All I do is go back over the past. What I said. What I did and didn’t do. How we laughed and when we cried. Words are not enough these days, so anything I try to write down about you seems like some cheap Coles notes. The kind that races over the beauty of the original work. You get the gist but not the impact. You can’t reduce a life to fit on the page.

All I do is go back over the past. What I said. What I did and didn’t do. How we laughed and when we cried. Words are not enough these days, so anything I try to write down about you seems like some cheap Coles notes. The kind that races over the beauty of the original work. You get the gist but not the impact. You can’t reduce a life to fit on the page.

I know this. Nonetheless, I sometimes find it hard to bear.

Here is how I tried, anyway:

(April 8th, 2017. St. Stephen’s-on-the-Hill United Church. Funeral service of remembrance for Irene (Renie) Phyllis Krook nee King. Four loved ones speak. I am the last.)

These are difficult times. The understatement of the year.

I make my living as a writer, so one might assume that figuring out what to say today would come naturally. But, I have never experienced a writer’s block like this. The desert hasn’t gone dry. The ground is flooded and I’m drowning in too much of everything, unable to feel which way is up.

Though I asked to be up here today, the task at hand seems impossible for many reasons. Three in particular come to mind. One is that none of this feels real. My grandmother seems as vibrant and alive in my mind as she did in every room she occupied—so much so that I haven’t been able to grasp her absence. I knew I would be without her one day. But knowing and understanding are very different things.

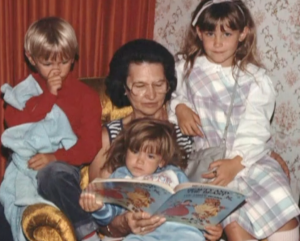

Reason number two is that her presence in my life was constant, my memories of her woven so tightly into the fabric of my being that it’s difficult to pull them out without the whole thing unraveling. Her home in Mississauga was a sanctuary for me and, I would assume, my siblings as well. We grew up there. This is the place where we fought over who got to sit beside Grandma at dinner, in the car, around the high-back chair for story time. She brought in bunk beds for us to sleep in the kids’ room, with a race car bed for my brother. She had porridge ready for me every morning, with raisins and brown sugar, and she always made sure it wasn’t too hot or too cold. In the summertime, she’d show us how to pick berries from the Saskatoon tree and lettuce from the garden, which we’d use to make little wraps (before gluten-free was ever a trend). She’d play games with us in the pool, pretending we were mermaids (my brother, a sea horse) that she would capture and put in the dungeon, from which she always let us escape so the chase could begin again. She told us stories about “the old days” and sang songs with lyrics she couldn’t quite remember, so for the longest time I thought most of the music from that era had “da-da-da-da” in it. She taught me to play crib, and every time her pegs passed mine, she’d say, “I’m rooting for you to win.” She played Pictionary with us, and Scrabble and Boggle and hide-and-seek. Summer vacations meant we’d each get a week at Grandma’s house—which, when you grow up in a family of six, is a really big deal. I’d have seven whole days with her, all to myself. We’d go shopping and to the movies, play mini golf and cards, then curl up with her to watch Wheel of Fortune and Jeopardy at the end of a day. But whether you spent time with her one-on-one or in a crowd, she always had a way of making you feel important, like you were the only one in the room. You were special.

Reason number two is that her presence in my life was constant, my memories of her woven so tightly into the fabric of my being that it’s difficult to pull them out without the whole thing unraveling. Her home in Mississauga was a sanctuary for me and, I would assume, my siblings as well. We grew up there. This is the place where we fought over who got to sit beside Grandma at dinner, in the car, around the high-back chair for story time. She brought in bunk beds for us to sleep in the kids’ room, with a race car bed for my brother. She had porridge ready for me every morning, with raisins and brown sugar, and she always made sure it wasn’t too hot or too cold. In the summertime, she’d show us how to pick berries from the Saskatoon tree and lettuce from the garden, which we’d use to make little wraps (before gluten-free was ever a trend). She’d play games with us in the pool, pretending we were mermaids (my brother, a sea horse) that she would capture and put in the dungeon, from which she always let us escape so the chase could begin again. She told us stories about “the old days” and sang songs with lyrics she couldn’t quite remember, so for the longest time I thought most of the music from that era had “da-da-da-da” in it. She taught me to play crib, and every time her pegs passed mine, she’d say, “I’m rooting for you to win.” She played Pictionary with us, and Scrabble and Boggle and hide-and-seek. Summer vacations meant we’d each get a week at Grandma’s house—which, when you grow up in a family of six, is a really big deal. I’d have seven whole days with her, all to myself. We’d go shopping and to the movies, play mini golf and cards, then curl up with her to watch Wheel of Fortune and Jeopardy at the end of a day. But whether you spent time with her one-on-one or in a crowd, she always had a way of making you feel important, like you were the only one in the room. You were special.

When I think of all of these things, they feel like insignificant remembrances in the scope someone’s whole life. They’re too small. But then I realize, that’s what it’s all about, isn’t it? My grandmother understood that to live a good life, you have to show up in all the small moments. Be present. Make space for others. Root for them to win. Never let too much time pass between a phone call, a smile, a card game or a meal. Love is in the details.

The amount of lessons I’ve learned from my grandmother is incalculable, really. I can’t always pick them out, but I see the pattern they make, one that reflects an energy and enthusiasm for what’s next.

Before she moved out to Calgary in August of last year, I pulled her aside. I told her I loved her, that it would be hard to be so far apart. And then I asked for advice, anything she could tell me about life that I could soak up and carry forward into mine.

“Marriage is for life,” she said to me. “If you pick the wrong partner, it will seem very long. If you choose right, nothing will be long enough.”

This brings me to reason number three, why I’ve struggled with what to say today. Because what’s true for marriage is true for family. With her, no amount of time would have ever been long enough.