Martin Luther King Jr. once said, “Faith is taking the first step even when you don’t see the whole staircase.”

Martin Luther King Jr. once said, “Faith is taking the first step even when you don’t see the whole staircase.”

I’ll be the first to admit the lack of this quality in my life. I have it in kernels, but with people, projects, promises—if I can’t figure out both the end game and how to get there, I’m skeptical at best to keep moving forward. At worst, I turn and bail. In relationships, if I lose sight of a future together, I let go in inches, checked out and waiting for the end explosion. For professional ventures, I need to get a sense of how my part impacts the whole organization, or I feel listless and unmotivated. Promises, well, I’ve come to realize I just don’t make them. Who knows when the wind will change and where I’ll end up.

I’m the same with writing. Whether a blog post or a novel, I need to plot the entire story before I begin and follow that map with linear precision, step by step. For as long as I can remember, that’s the way I’ve been.

Someone recently pointed out how often I write about the desire for control, for a clear-cut plan (here, here and here, to list a few). So, it’s obvious I’m highly aware of this tendency. I’ve just never thought about it as a problem.

Then I headed out to California for my self-imposed writer’s retreat. (One has to be careful about the punctuation here, because many assumed it was a writers’ retreat, picturing me meeting up with others for a whirlwind week of communal time in front of notepads, computers and thick-rimmed glasses with my mysterious writer friends. Perhaps an iconic Scotch or two. Not so. It was just me.)

The idea was to get a kick-start for a new novel, enough of a boost to carry me through the busyness of a packed life back home that usually left me too tired to create for myself. I needed a targeted drive to keep me writing.

Before I left, I set out a definitive structure for each day. Starting with a 7am run and quick breakfast, I’d hammer on the keys for three hours during my first of three writing sessions, taking short breaks in between, producing no less than 1,000 words each session. In the evening, I would relax with a short work out before nestling into bed with a book.

Now, I know this would be most people’s vacation hell, but to me, it sounded like just the opposite. Surrounded by warm weather, towering palm trees and the ocean, I would finally be free to think and create in peace—as long as I had a plan to keep me on track, of course.

And the first two days went well. I was on track to meet all of my goals. I went to bed that night swelling with pride at the column of check marks I had achieved. Well, you can probably guess what happened next. It’s an old lesson. Pride. Cliff. Edge. Me.

Day number three hit me like a wrecking ball (thank you, Miley, for making that image now supremely unusable). My body felt exhausted from the early morning runs and late night gym sessions; the action in my novel was stuck in a lull, somewhere between what had happened off the page and what would happen to restart the character’s hearts; the words that did come out felt jarring and stiffly chronological—there was no flow. No natural rhythm. No poetry. It is the worst way to drag yourself through writing, letter by letter, as if crawling through the desert chained to a weight when you have just enough strength for one foothold at a time.

I decided to take a break, head to the beach, vowing to come back more inspired that night. I ended up in a local pub, eating some of San Diego’s best tacos, throwing back a couple of ciders (which I got ID’d for—so, points) and people watching. I walked back to my hotel while the sun set behind me, crossed off all the things on my list I hadn’t completed that day and crawled into bed, dejected and bogged down by a head full of the thick sludge that comes with a block. And cider.

The next day, I slept in. I skipped the run. But I was determined, putting only one thing on my to-do list: write the part you are most excited about.

It was the scene that had inspired the entire story: A girl, high on the bluffs overlooking the rocky coast of a lake. She waves, the movement of her hand catching the eye of a boy out in a canoe. His father paddles in the stern. The boy raises his hand to wave back, but stops, watching someone approaching the girl from behind. A hand closes over her mouth. Arms wrap around her petite frame and drag her away. As hard as the boy paddles to get to shore, to get to her, he is already too late. She is gone.

I have seen this play out in my head, over and over, for the last three years (where are the medals for writers who don’t go crazy carrying bizarre stories around with them 24/7?). My intention was to end the week writing this scene, riding out the high it would produce all the way back home to Toronto.

So, I took a deep breath and I wrote it. Out of order. Mad, rebel style. I wasn’t sure exactly how or why the characters would get to that moment, only that they had to.

And a strange thing happened. I fell in love with it, the whole process. I reveled in not knowing. In taking my writing in bites, unconcerned with the whole meal, just savouring each scene. Rather than starting from chapter one and moving through each one, I picked parts I was passionate about, ones that made my own heart race with the panic of what might happen to the characters. I chose patches to focus my energy on, unconcerned with how I would stitch them together later on.

When I stopped to wonder why, I realized that the mind isn’t linear, thinking this then that, moving only in one direction. It prances around from past to present to hopes for the future. Playing out memories, worrying about what to make for dinner, then yanking itself back to say to the customs officer, “No, sir, nothing to claim.” So if the mind isn’t linear, why should the writing process be? Letting go of that way of thinking was being freed from unnatural chains that otherwise forced me to walk backward on my hands (something I can actually manage, but not for long periods of time).

I met my 18,000 word goal. And then I surpassed it. The story is incomplete, in pieces, leading up to the girl up on the bluffs, but it’s real and alive and something I’m more than eager to keep working on.

Most of what we consume these days—movies, television, books—they’re told in this linear fashion, so we’re used to that format and writer’s often try to recreate it as they experience it. When we stumble upon a story told in jumbles or even backward (like the classic physiological thriller Memento), we find it hard but exhilarating to piece it all together.

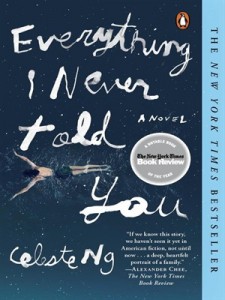

Like the book I read on vacation, called Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng, about a Chinese American family and the balancing act that keeps them together—but which ultimately tears them apart. I struggled with the first chapter or so. No, I struggled with the first few words. “Lydia is dead. But they don’t know this yet. 1977, May 3, six thirty in the morning, no one knows anything but this innocuous fact: Lydia is late for breakfast.”

Like the book I read on vacation, called Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng, about a Chinese American family and the balancing act that keeps them together—but which ultimately tears them apart. I struggled with the first chapter or so. No, I struggled with the first few words. “Lydia is dead. But they don’t know this yet. 1977, May 3, six thirty in the morning, no one knows anything but this innocuous fact: Lydia is late for breakfast.”

Starting with the end, jumping time periods and perspectives, told in the voice of an omniscient narrator—I find it the hardest to read (and, I assume, to write), because it does what we call “head jumping” with a strange sense of legitimacy.

But as the story blossomed, the bare bones presented in those first few words fleshed out, I discovered the story’s beauty in tandem with the breakthrough in my own writing. The writer started with her inspiration. Her what. A scene, a thought, a seed that planted inside her and spread, never letting go. As a reader, I experienced her discovery of the why along with the writer. Non-linear, bits and pieces that came to life as I pulled them together in my mind, like following a maze of roots to the base of a tree. It seemed natural, and yet magical.

And, I realized, I need to more of that. In writing. In life. Whether experiencing or creating, I need to let go of the linear and just jump in. Even if that’s the middle and you don’t know how you got there or how to get out, or stay in, or ways to have it all make sense. There’s freedom in focusing on the bits that evoke passion and excitement, allowing the other pieces to come a little later, if they have to. There doesn’t have to be an entire staircase every time. All you need is a step.